Monday Poster Session

Category: Liver

P3147 - From Liver to Nasal Drip: Epistaxis Unveils Itself as a Novel Complication in MASH Cirrhosis

Monday, October 28, 2024

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM ET

Location: Exhibit Hall E

Has Audio

John Michael Vincent Coralde, MD

Southwest Healthcare MEC

Murrieta, CA

Presenting Author(s)

John Michael Vincent Coralde, MD1, Sukhman Dhaliwal, DO2, Sandesh Karki, MD2, Ali Ghorbani, DO2, Sina Bagheri, DO2, Evelyn Aldana, MD2, Indraneel Chakrabarty, MD, MA2

1Southwest Healthcare MEC, Murrieta, CA; 2Southwest Healthcare MEC, Temecula, CA

Introduction: Epistaxis is a common symptom in patients with MASH (Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis) cirrhosis, with a prevalence of 10-25%. This is higher than the prevalence of epistaxis in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis or in the general population. The most common risk factors for epistaxis with patients with MASH cirrhosis are portal Hypertension, coagulopathy, and platelet dysfunction according to Terracciano et al. Epistaxis can be a significant clinical problem in patients with MASH cirrhosis. It can lead to anemia, hemodynamic instability, and even death.

Case Description/Methods:

A 69-year-old female with a history of IBS-C presented with abdominal bloating, melena and bright red blood per rectum. Interestingly, she admitted to frequent nosebleeds that would occur multiple times weekly starting one month prior. She was hemodynamically stable on her initial vital signs. Initial laboratory testing revealed hemoglobin 9.6 with baseline hgb of 13.0. Platelets of 90,000. No significant coagulopathy with hepatocelluar pattern of transaminitis. She was started on IV protonix. Her EGD showed Grade 1 varices in the lower third of esophagus with no recent stigmata of bleeding, moderate portal gastropathy, non-erosive gastropathy. Her colonoscopy showed several small non-bleeding sessile polyps, Grade II external and internal hemorrhoids. On discharge, patient was educated on changes to diet, weight reduction, as well as the importance of strict lipid, glycemic and blood pressure control.

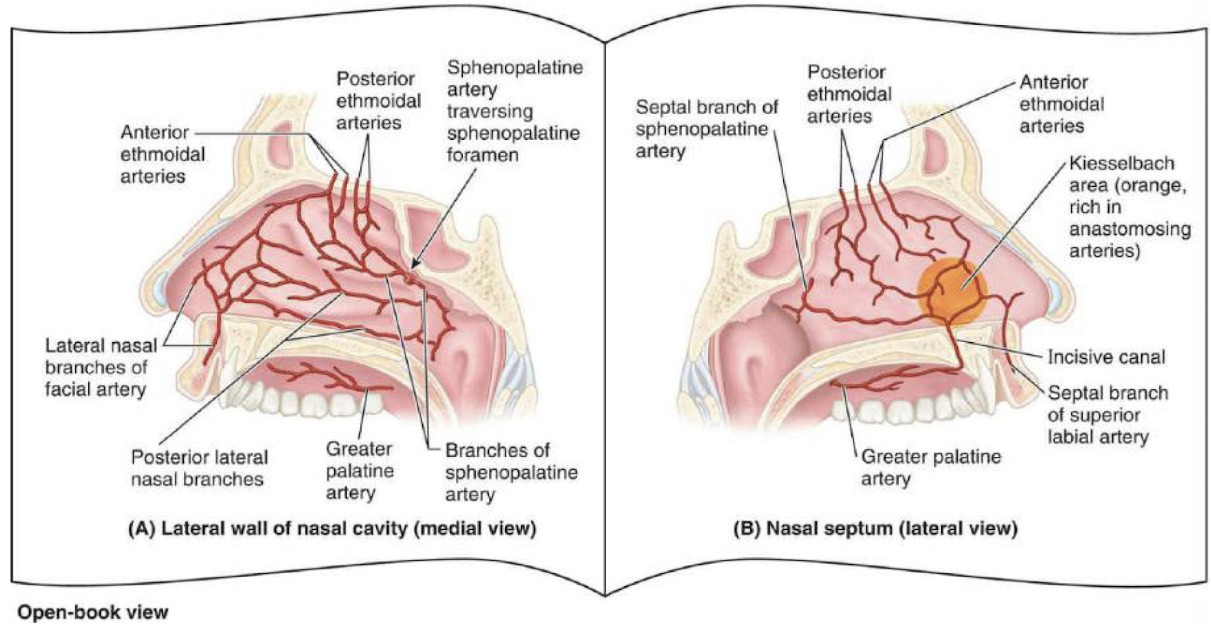

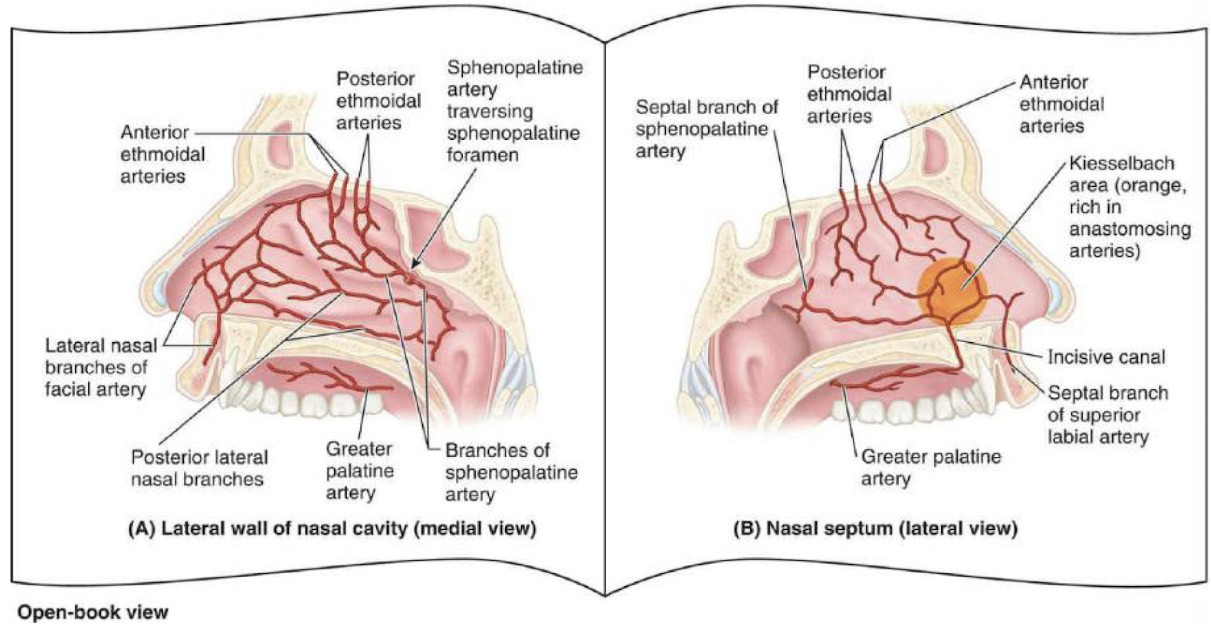

Discussion: Patients with chronic liver disease exhibited a higher incidence of epistaxis, and the severity of nosebleeds correlated with the degree of liver impairment according to Aricil et.al. This study suggests that nosebleeds could serve as an early indicator of liver dysfunction, prompting timely intervention. According to the research conducted by Camus et al., the diagnosis of epistaxis as the source of bleeding was identified in 4.3% of cirrhotic patients suspected of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. This prevalence escalated to 15.3% in a subgroup of cirrhotic patients experiencing hemorrhage after hospitalization due to worsening liver disease, despite lacking signs of UGIB upon admission. In our case, the patient experienced a nosebleed confined to the posterior region, it resulted in a notable decline in her hemoglobin levels. Healthcare providers overseeing patients with ESLD should be mindful that posterior nasopharyngeal epistaxis may simulate a severe UGIB.

Disclosures:

John Michael Vincent Coralde, MD1, Sukhman Dhaliwal, DO2, Sandesh Karki, MD2, Ali Ghorbani, DO2, Sina Bagheri, DO2, Evelyn Aldana, MD2, Indraneel Chakrabarty, MD, MA2. P3147 - From Liver to Nasal Drip: Epistaxis Unveils Itself as a Novel Complication in MASH Cirrhosis, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Southwest Healthcare MEC, Murrieta, CA; 2Southwest Healthcare MEC, Temecula, CA

Introduction: Epistaxis is a common symptom in patients with MASH (Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis) cirrhosis, with a prevalence of 10-25%. This is higher than the prevalence of epistaxis in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis or in the general population. The most common risk factors for epistaxis with patients with MASH cirrhosis are portal Hypertension, coagulopathy, and platelet dysfunction according to Terracciano et al. Epistaxis can be a significant clinical problem in patients with MASH cirrhosis. It can lead to anemia, hemodynamic instability, and even death.

Case Description/Methods:

A 69-year-old female with a history of IBS-C presented with abdominal bloating, melena and bright red blood per rectum. Interestingly, she admitted to frequent nosebleeds that would occur multiple times weekly starting one month prior. She was hemodynamically stable on her initial vital signs. Initial laboratory testing revealed hemoglobin 9.6 with baseline hgb of 13.0. Platelets of 90,000. No significant coagulopathy with hepatocelluar pattern of transaminitis. She was started on IV protonix. Her EGD showed Grade 1 varices in the lower third of esophagus with no recent stigmata of bleeding, moderate portal gastropathy, non-erosive gastropathy. Her colonoscopy showed several small non-bleeding sessile polyps, Grade II external and internal hemorrhoids. On discharge, patient was educated on changes to diet, weight reduction, as well as the importance of strict lipid, glycemic and blood pressure control.

Discussion: Patients with chronic liver disease exhibited a higher incidence of epistaxis, and the severity of nosebleeds correlated with the degree of liver impairment according to Aricil et.al. This study suggests that nosebleeds could serve as an early indicator of liver dysfunction, prompting timely intervention. According to the research conducted by Camus et al., the diagnosis of epistaxis as the source of bleeding was identified in 4.3% of cirrhotic patients suspected of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. This prevalence escalated to 15.3% in a subgroup of cirrhotic patients experiencing hemorrhage after hospitalization due to worsening liver disease, despite lacking signs of UGIB upon admission. In our case, the patient experienced a nosebleed confined to the posterior region, it resulted in a notable decline in her hemoglobin levels. Healthcare providers overseeing patients with ESLD should be mindful that posterior nasopharyngeal epistaxis may simulate a severe UGIB.

Figure: (Fig. 1) Lateral and medial (septal) arterial vasculature of nasal cavity with anterior coronal section of nasal cavity to appreciate the extensive vascularity of the nasal cavity.

Disclosures:

John Michael Vincent Coralde indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sukhman Dhaliwal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sandesh Karki indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Ali Ghorbani indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sina Bagheri indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Evelyn Aldana indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Indraneel Chakrabarty indicated no relevant financial relationships.

John Michael Vincent Coralde, MD1, Sukhman Dhaliwal, DO2, Sandesh Karki, MD2, Ali Ghorbani, DO2, Sina Bagheri, DO2, Evelyn Aldana, MD2, Indraneel Chakrabarty, MD, MA2. P3147 - From Liver to Nasal Drip: Epistaxis Unveils Itself as a Novel Complication in MASH Cirrhosis, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.