Monday Poster Session

Category: Esophagus

P2241 - A Case of Fistulizing, Lower Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Following Heller Myotomy With Fundoplication in a Patient With Achalasia

Monday, October 28, 2024

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM ET

Location: Exhibit Hall E

Has Audio

Danzhu Zhao, DO

University of Connecticut Health Center

WEST HARTFORD, CT

Presenting Author(s)

Danzhu Zhao, DO, Akaash Mittal, MD, Haleh Vaziri, MD

University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT

Introduction: Achalasia is a risk factor for esophageal carcinomas, particularly esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)(1). ESCC is generally proximally located and less common than esophageal adenocarcinomas. We present a patient found to have lower ESCC with fistulization to the upper stomach due to a prior Heller myotomy (HM) and fundoplication for achalasia.

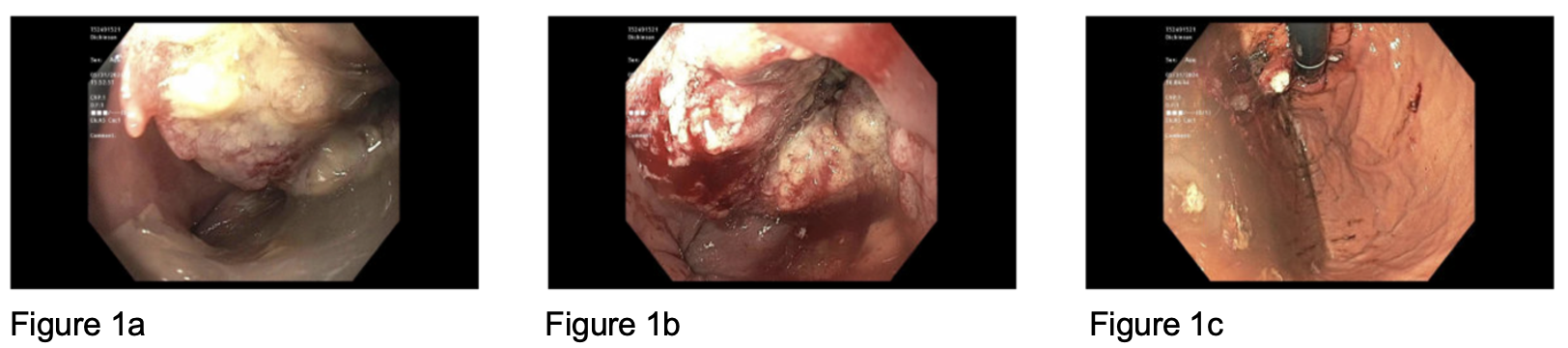

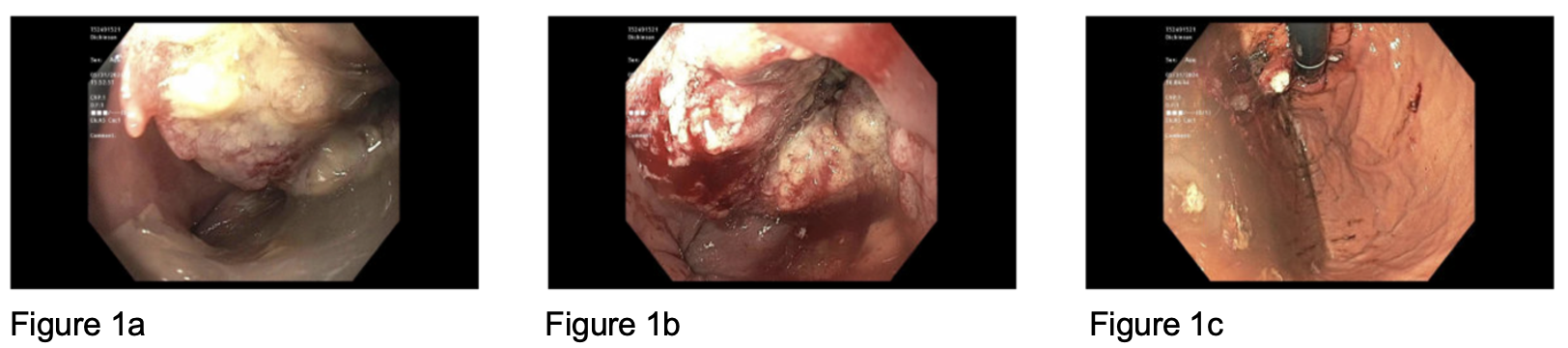

Case Description/Methods: A 55-year-old female with a history of achalasia and HM (2006) presented to the ED with subacute headache and right arm weakness. She had chronic dysphagia despite previous HM with weeks of worsening regurgitation despite proton pump inhibitor use. She consumed minimal alcohol and denied tobacco use. Her vitals, labs, and physical exam were unremarkable. Brain imaging revealed a 3.3cm by 3.2cm left parietal lobe mass. CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed an inferior mediastinal mass originating from either the herniated portion of gastric fundus or distal esophagus, though the former was favored. Invasion to liver and metastatic lesions to bone and adrenal glands were also noted. Upper endoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, fungating mass 4 cm above the Z line with a fistula-like tract emanating from the middle of the mass (Figure 1a and 1b). Retroflexion showed a fungating mass partially covered by food (Figure 1c). Mass biopsies revealed invasive ESCC. She was discharged with GI, oncology, and neurosurgery follow up.

Discussion: ESCC rarely involves the lower third of the esophagus. Achalasia is a risk factor for ESCC but the symptoms may overlap, delaying timely diagnosis of ESCC. A high index of suspicion and symptom monitoring are required to prevent this, particularly in the absence of formal screening recommendations. Our case was unique in that the esophageal mass invaded the upper stomach without involving the esophago-gastric junction. This likely resulted from the patient’s HM and fundoplication that raised her upper stomach to the involved esophageal area years earlier. 2020 ACG guidelines suggested against routine cancer screening in patients with achalasia, though the quality of evidence was low. Experts have proposed surveillance EGDs every 3 years in patients with achalasia for over 10 years(2).

References:

1. Nesteruk et al. Achalasia and associated esophageal cancer risk: What lessons can we learn from the molecular analysis of Barrett’s–associated adenocarcinoma? 2019 Dec 1;1872(2):188291.

2. Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Editorial: Cancer surveillance in achalasia: better late than never? 2010 Oct;105(10):2150–2.

Disclosures:

Danzhu Zhao, DO, Akaash Mittal, MD, Haleh Vaziri, MD. P2241 - A Case of Fistulizing, Lower Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Following Heller Myotomy With Fundoplication in a Patient With Achalasia, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.

University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT

Introduction: Achalasia is a risk factor for esophageal carcinomas, particularly esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)(1). ESCC is generally proximally located and less common than esophageal adenocarcinomas. We present a patient found to have lower ESCC with fistulization to the upper stomach due to a prior Heller myotomy (HM) and fundoplication for achalasia.

Case Description/Methods: A 55-year-old female with a history of achalasia and HM (2006) presented to the ED with subacute headache and right arm weakness. She had chronic dysphagia despite previous HM with weeks of worsening regurgitation despite proton pump inhibitor use. She consumed minimal alcohol and denied tobacco use. Her vitals, labs, and physical exam were unremarkable. Brain imaging revealed a 3.3cm by 3.2cm left parietal lobe mass. CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed an inferior mediastinal mass originating from either the herniated portion of gastric fundus or distal esophagus, though the former was favored. Invasion to liver and metastatic lesions to bone and adrenal glands were also noted. Upper endoscopy (EGD) revealed a large, fungating mass 4 cm above the Z line with a fistula-like tract emanating from the middle of the mass (Figure 1a and 1b). Retroflexion showed a fungating mass partially covered by food (Figure 1c). Mass biopsies revealed invasive ESCC. She was discharged with GI, oncology, and neurosurgery follow up.

Discussion: ESCC rarely involves the lower third of the esophagus. Achalasia is a risk factor for ESCC but the symptoms may overlap, delaying timely diagnosis of ESCC. A high index of suspicion and symptom monitoring are required to prevent this, particularly in the absence of formal screening recommendations. Our case was unique in that the esophageal mass invaded the upper stomach without involving the esophago-gastric junction. This likely resulted from the patient’s HM and fundoplication that raised her upper stomach to the involved esophageal area years earlier. 2020 ACG guidelines suggested against routine cancer screening in patients with achalasia, though the quality of evidence was low. Experts have proposed surveillance EGDs every 3 years in patients with achalasia for over 10 years(2).

References:

1. Nesteruk et al. Achalasia and associated esophageal cancer risk: What lessons can we learn from the molecular analysis of Barrett’s–associated adenocarcinoma? 2019 Dec 1;1872(2):188291.

2. Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Editorial: Cancer surveillance in achalasia: better late than never? 2010 Oct;105(10):2150–2.

Figure: Figure 1a. A large, fungating mass about 4 cm above the Z line. The mass was nonobstructing and partially circumferential (involving one-third of the lumen circumference).

Figure 1b. There was a fistula-like tract with the opening in the middle of the mass.

Figure 1c. A fungating mass was found in the gastric fundus mostly covered by food.

Figure 1b. There was a fistula-like tract with the opening in the middle of the mass.

Figure 1c. A fungating mass was found in the gastric fundus mostly covered by food.

Disclosures:

Danzhu Zhao indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Akaash Mittal indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Haleh Vaziri indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Danzhu Zhao, DO, Akaash Mittal, MD, Haleh Vaziri, MD. P2241 - A Case of Fistulizing, Lower Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Following Heller Myotomy With Fundoplication in a Patient With Achalasia, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.