Sunday Poster Session

Category: Liver

P1274 - Menorrhagia Secondary to Uterovaginal Varices

Sunday, October 27, 2024

3:30 PM - 7:00 PM ET

Location: Exhibit Hall E

Has Audio

Benjamin E. Hoffman, MD

Tufts Medical Center

Boston, MA

Presenting Author(s)

Benjamin E. Hoffman, MD, Tamiru B. Berake, MD, Beverly Wong, MD, Luke Higgins, MD, Anjan Devaraj, MD, Fredric Gordon, MD

Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA

Introduction: A rare case of menorrhagia is secondary to uterovaginal varices with fewer than 15 cases described.1 We present a case of menorrhagia secondary to uterovaginal varices in the setting of cirrhosis to further characterize this rare presentation.

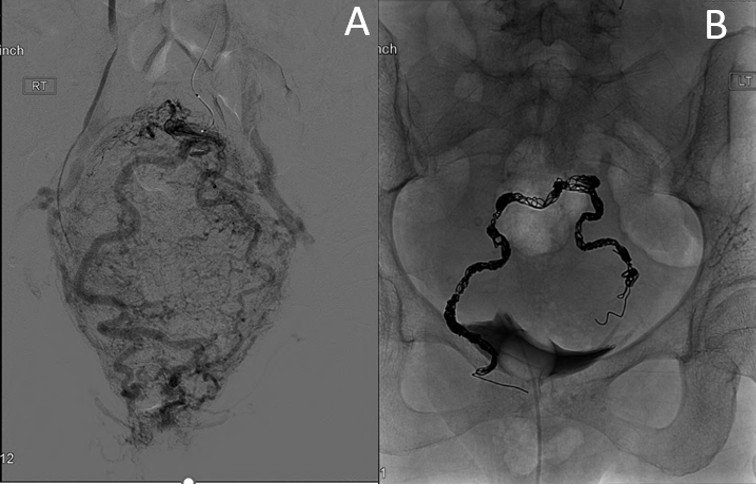

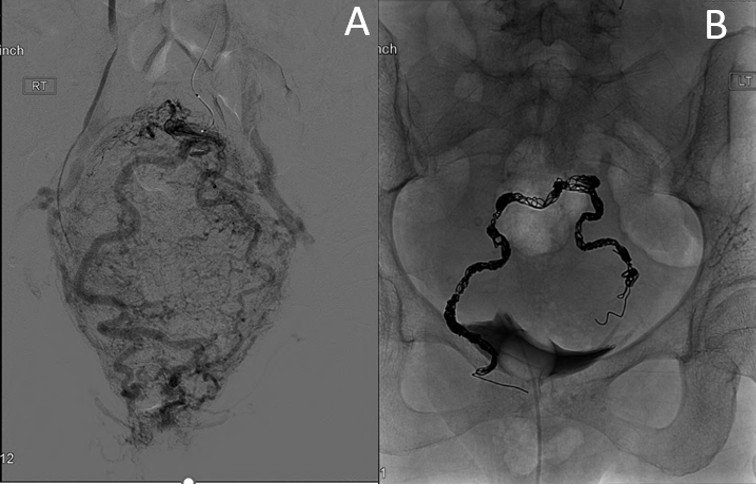

Case Description/Methods: A 39-year-old female with alcohol associated cirrhosis (MELD 23) complicated by esophageal and rectal varices presented with transfusion-dependent menorrhagia and hypotension. Labs on presentation were notable for hemoglobin 3.7 g/dL, platelets 48 K/uL, and INR 1.57. Transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic examination did not identify a culprit lesion. She was non-candidate for oral contraceptives or hysterectomy due to cirrhosis. She underwent uterine artery ablation without improvement. CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showed large inferior rectal varices. Venography revealed retrograde flow in the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) with engorged uterovaginal and rectal varices. Embolization of bilateral pelvic branches of the distal IMV was successful with resolution of menorrhagia.

Discussion: Menorrhagia secondary to uterovaginal varices is a rare complication of cirrhosis and can be challenging to diagnose given both its rarity and spectrum of disease presentation. The acuity of bleeding can vary from overt hemorrhagic shock to bleeding over months that may mimic other uterine pathologies.1-2 Therefore, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for uterovaginal varices as etiology of menorrhagia in patients with known cirrhosis. Patients who have had prior hysterectomy are at higher risk of developing vaginal varices due to a decrease in venous capacitance through the loss of the uterine venous plexus, though our patient had an intact uterus. Management of variceal vaginal bleeding aims to reduce portal pressure, often through interventions such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or liver transplant. Temporary measures such as tamponade and embolization are usually necessary for immediate control; our patient had no recurrence with embolization alone.

1. Smith JK et al. Ectopic Vaginal Varices With Hemorrhage After Hysterectomy. ACG Case Rep J. 2022;9(10)

2. Glick JE et al. An Unusual Cause of Vaginal Bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(3):322-323

Disclosures:

Benjamin E. Hoffman, MD, Tamiru B. Berake, MD, Beverly Wong, MD, Luke Higgins, MD, Anjan Devaraj, MD, Fredric Gordon, MD. P1274 - Menorrhagia Secondary to Uterovaginal Varices, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.

Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA

Introduction: A rare case of menorrhagia is secondary to uterovaginal varices with fewer than 15 cases described.1 We present a case of menorrhagia secondary to uterovaginal varices in the setting of cirrhosis to further characterize this rare presentation.

Case Description/Methods: A 39-year-old female with alcohol associated cirrhosis (MELD 23) complicated by esophageal and rectal varices presented with transfusion-dependent menorrhagia and hypotension. Labs on presentation were notable for hemoglobin 3.7 g/dL, platelets 48 K/uL, and INR 1.57. Transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic examination did not identify a culprit lesion. She was non-candidate for oral contraceptives or hysterectomy due to cirrhosis. She underwent uterine artery ablation without improvement. CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showed large inferior rectal varices. Venography revealed retrograde flow in the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) with engorged uterovaginal and rectal varices. Embolization of bilateral pelvic branches of the distal IMV was successful with resolution of menorrhagia.

Discussion: Menorrhagia secondary to uterovaginal varices is a rare complication of cirrhosis and can be challenging to diagnose given both its rarity and spectrum of disease presentation. The acuity of bleeding can vary from overt hemorrhagic shock to bleeding over months that may mimic other uterine pathologies.1-2 Therefore, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for uterovaginal varices as etiology of menorrhagia in patients with known cirrhosis. Patients who have had prior hysterectomy are at higher risk of developing vaginal varices due to a decrease in venous capacitance through the loss of the uterine venous plexus, though our patient had an intact uterus. Management of variceal vaginal bleeding aims to reduce portal pressure, often through interventions such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or liver transplant. Temporary measures such as tamponade and embolization are usually necessary for immediate control; our patient had no recurrence with embolization alone.

1. Smith JK et al. Ectopic Vaginal Varices With Hemorrhage After Hysterectomy. ACG Case Rep J. 2022;9(10)

2. Glick JE et al. An Unusual Cause of Vaginal Bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2016;51(3):322-323

Figure: Figure 1. IMV distal portal venogram with uterovaginal varices. A. Delayed phase showing drainage into the vaginal venous plexus and systemic circulation (iliac veins). B. Following embolization of bilateral pelvic branches.

Disclosures:

Benjamin Hoffman indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Tamiru Berake indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Beverly Wong indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Luke Higgins indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Anjan Devaraj indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Fredric Gordon indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Benjamin E. Hoffman, MD, Tamiru B. Berake, MD, Beverly Wong, MD, Luke Higgins, MD, Anjan Devaraj, MD, Fredric Gordon, MD. P1274 - Menorrhagia Secondary to Uterovaginal Varices, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.