Tuesday Poster Session

Category: Biliary/Pancreas

P3533 - Choledochal Varices: A Rare Sequela of Portal Hypertension

Tuesday, October 29, 2024

10:30 AM - 4:00 PM ET

Location: Exhibit Hall E

Has Audio

- AV

Adam Vinall, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center

San Antonio, TX

Presenting Author(s)

Adam Vinall, MD, Peter Stawinski, MD, Karolina Dziadkoweic, MD, Jason Rocha, MD

University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX

Introduction: Hemobilia, a rare but potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, can result from trauma, iatrogenic injuries from procedures like ERCP or liver biopsy, tumors, vascular malformations, or inflammatory conditions. Here, we present a rare case of hemobilia from choledochal varices in a patient with portal hypertension and a retained biliary stent.

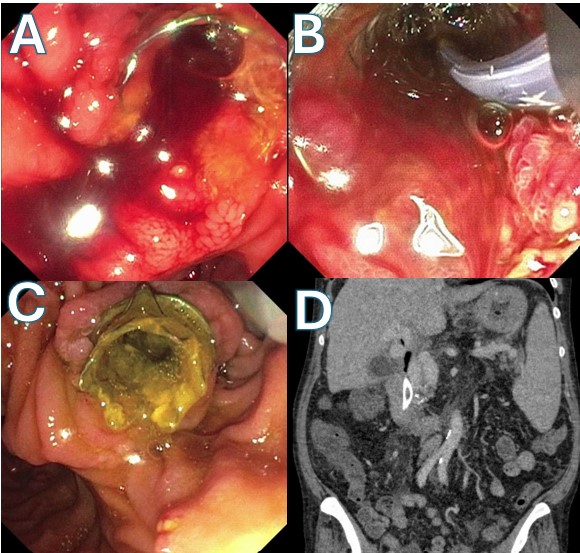

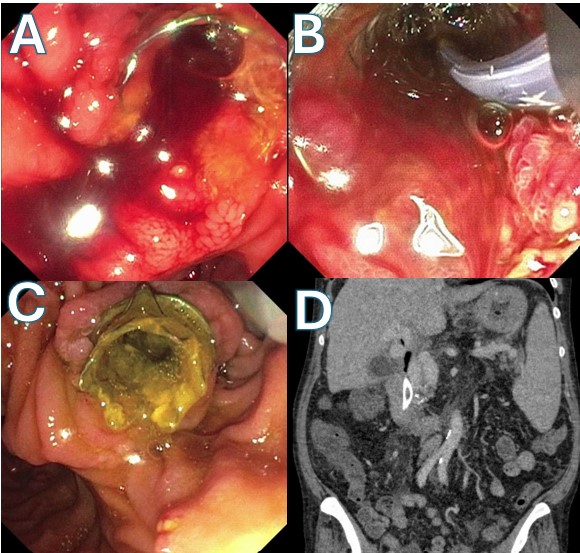

Case Description/Methods: A 45-year-old female with alcohol-associated cirrhosis, esophageal varices, and chronic pancreatitis presented with one day of melena and two episodes of hematemesis. Four years prior, she had an ERCP with metal stent placement for biliary stricture, and an attempt to remove the stent two weeks earlier resulted in massive hemobilia, requiring stent replacement. On arrival, she was febrile (39.3°C), with a heart rate of 140 and blood pressure of 93/71. She had generalized abdominal tenderness. Her hemoglobin was 9.1 (down from 11.4 two weeks prior), platelet count was 96, and liver function tests were mildly elevated (AST 58, ALT 70, total bilirubin 2.6). A CT angiogram showed cirrhosis, portosystemic varices, and splenomegaly (Image D). Upper endoscopy revealed no gastric or esophageal bleeding, but a metal stent in the ampulla of the duodenum was actively draining pus, bile, and blood (Image A). A fully covered metal stent was placed within the existing stent (Image B), achieving hemostasis. Due to suspected bleeding from portosystemic collaterals fistulizing with the biliary tree, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was performed. Repeat ERCP post-TIPS showed patent metal stents without hemobilia (Image C).

Discussion: In this case, proximal biliary stent migration and retention over multiple years led to the development of choledochal varices and fistulization with the biliary tree in a patient with severe portal hypertension. Attempted removal of the stent led to massive hemobilia which necessitated repeat stent placement. This case highlights the need for high index of suspicion for biliary varices when approaching the patient with portal hypertension, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and a history of biliary instrumentation. Stent removal should be done with extreme caution in these patients, as the stent acts to tamponade the varices. In patients with hemobilia from choledochal varices, endoscopic treatments can provide immediate hemostasis, though more definite management should focus on reversal of portal hypertension with TIPS or liver transplantation.

Disclosures:

Adam Vinall, MD, Peter Stawinski, MD, Karolina Dziadkoweic, MD, Jason Rocha, MD. P3533 - Choledochal Varices: A Rare Sequela of Portal Hypertension, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.

University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX

Introduction: Hemobilia, a rare but potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, can result from trauma, iatrogenic injuries from procedures like ERCP or liver biopsy, tumors, vascular malformations, or inflammatory conditions. Here, we present a rare case of hemobilia from choledochal varices in a patient with portal hypertension and a retained biliary stent.

Case Description/Methods: A 45-year-old female with alcohol-associated cirrhosis, esophageal varices, and chronic pancreatitis presented with one day of melena and two episodes of hematemesis. Four years prior, she had an ERCP with metal stent placement for biliary stricture, and an attempt to remove the stent two weeks earlier resulted in massive hemobilia, requiring stent replacement. On arrival, she was febrile (39.3°C), with a heart rate of 140 and blood pressure of 93/71. She had generalized abdominal tenderness. Her hemoglobin was 9.1 (down from 11.4 two weeks prior), platelet count was 96, and liver function tests were mildly elevated (AST 58, ALT 70, total bilirubin 2.6). A CT angiogram showed cirrhosis, portosystemic varices, and splenomegaly (Image D). Upper endoscopy revealed no gastric or esophageal bleeding, but a metal stent in the ampulla of the duodenum was actively draining pus, bile, and blood (Image A). A fully covered metal stent was placed within the existing stent (Image B), achieving hemostasis. Due to suspected bleeding from portosystemic collaterals fistulizing with the biliary tree, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was performed. Repeat ERCP post-TIPS showed patent metal stents without hemobilia (Image C).

Discussion: In this case, proximal biliary stent migration and retention over multiple years led to the development of choledochal varices and fistulization with the biliary tree in a patient with severe portal hypertension. Attempted removal of the stent led to massive hemobilia which necessitated repeat stent placement. This case highlights the need for high index of suspicion for biliary varices when approaching the patient with portal hypertension, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and a history of biliary instrumentation. Stent removal should be done with extreme caution in these patients, as the stent acts to tamponade the varices. In patients with hemobilia from choledochal varices, endoscopic treatments can provide immediate hemostasis, though more definite management should focus on reversal of portal hypertension with TIPS or liver transplantation.

Figure: Image A. Metal stent at ampulla with blood and pus draining from the common bile duct.

Image B. A 60 mm long 10 mm deployed diameter fully covered metal stent was placed within the existing stent to control active bleeding.

Image C. Follow up ERCP after TIPS placement with resolution of hemobilia and two metal stents.

Image D. Stent seen in common bile duct with large varices at porta hepatis, originating from the portal vein.

Image B. A 60 mm long 10 mm deployed diameter fully covered metal stent was placed within the existing stent to control active bleeding.

Image C. Follow up ERCP after TIPS placement with resolution of hemobilia and two metal stents.

Image D. Stent seen in common bile duct with large varices at porta hepatis, originating from the portal vein.

Disclosures:

Adam Vinall indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Peter Stawinski indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Karolina Dziadkoweic indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Jason Rocha indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Adam Vinall, MD, Peter Stawinski, MD, Karolina Dziadkoweic, MD, Jason Rocha, MD. P3533 - Choledochal Varices: A Rare Sequela of Portal Hypertension, ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Gastroenterology.